The Thatcher Illusion

Ingredients

Your eyes

The below pictures on the computer screen.

Instructions

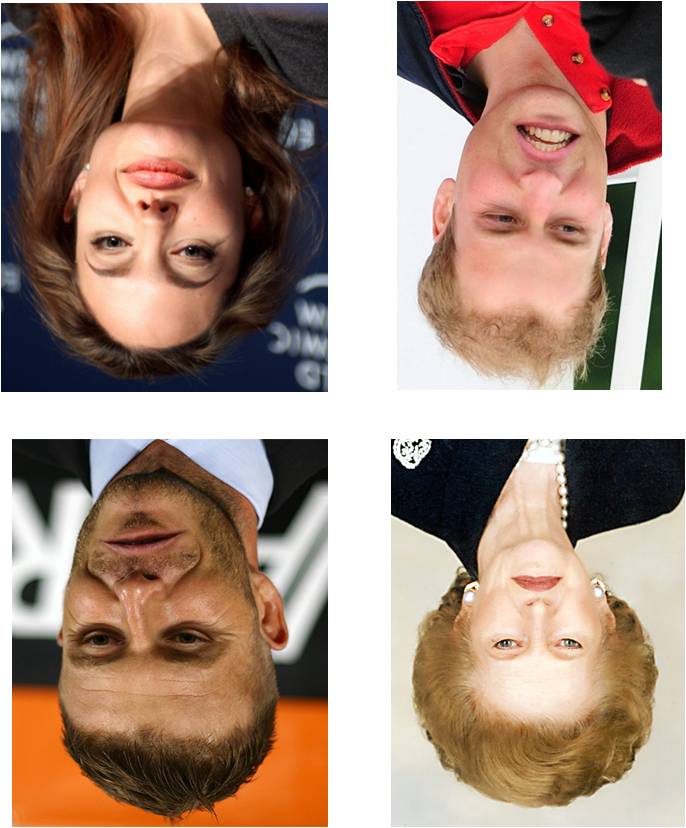

1. Stare at the upside down faces for about 10 seconds - Do you notice anything unusual? (Aside from the faces being upside down of course!)

1. Scroll down and look at the below image. Do you notice anything unusual now? These are exactly the same images, simply rotated round!

2.

Result

The people look pretty normal when upside down. However when the faces are the right way up, it is immediately apparent that they look a little odd, disgusting, grotesque.

Why? The eyes and mouth have been turned upside down in both images, but you probably only noticed that something is wrong when the image was the right way up.

Which part of the brain is responsible?

The medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate are involved in processing information from the eyes and mouth (the eyes and mouth give social and emotional cues).

The fusiform area and the lateral occipital cortex may also be involved in processing topsy turvy faces.

Explanation

The Thatcher illusion has caused quite a stir amongst both scientists and the public. We're still not exactly sure how the illusion works.

We know that our brains have developed a high sensitivity for recognising faces - so that we can tell the difference between individual's faces, like telling your mother, sister and a stranger apart.

But how does it do this? Researcher think your brain relies on how the face is configured, using information about features - like the distance between nose and mouth, or the distance between our eyes. But when a face is upside down, the brain is unable to process facial features as well - this is because we do not normally look at upside-down faces!

We haven't evolved to interpret the expression on upside down faces so we don't notice the changes in the eyes and mouth when they are the wrong way round.

So, something as seemingly simple as how you recognise your friend's face in a crowd is highly complex business - the configuration of the face, the proportions and the expression appear to provide people with important information about their origin, health, social interaction and social cues. Exactly how the brain perceives and processes the many different aspects of facial recognition and comprehension remains a controversial contention amongst neuroscientists.

This illusion therefore gives us a great example of much we have yet to learn about the brain, and also how our brain takes shortcuts - our senses are constantly bombarding our brains with all kinds of information on sight, tough, sound, smell and taste; and your brain cannot possibly process all of this information! It has to filter and decide which bits of information are important enough to be processed. This can sometimes cause our brains to make shortcuts and presumptions in perceptions, as seen with the Thatcher Illusion - we did not notice how odd and grotesque the faces were when they were upside down, but just presumed the eyes and mouth were in the correct orientation.

Why do scientists study this?

The Thatcher effect was discovered in 1980 by a perception scientist called Peter Thompson. He first created the illusion using the famous face of Margaret Thatcher, the Prime Minister at the time, who is remembered as a lady who was "not for turning" in her political and economical reforms!

Fun facts: The Thatcher effect is not just limited to humans - it was recently discovered that chimpanzees also fall for the Thatcher illusion. They only became very excited when looking at the grotesque upside down eyes and lips on a face that is right way up!

Our eyes and mouths provide very important social and emotional cues, and this illusion is an example of how our brains process these cues to form our perception of the world. Scientists are still trying to work out the precise neural circuitry that underlies the Thatcher effect.

People with prosopagnosia, a condition where they are unable to recognise faces, are quicker at spotting the upside-down Thatcherised faces! Prosopagnosiacs have damage to a region of the brain called the fusiform gyrus, and are unable to pick out their close friends or family's faces in a sea of strangers. However, they are able to recognise facial emotions and so, seem less affected by the Thatcher illusion.

On the other hand, people with autism find it difficult to receive and process social and emotional cues. They generally find it difficult to interact with people around them as they sometimes struggle to understand other people's feelings. Eyes and mouths provide us with lots of social and emotional cues, like telling if somebody is happy, sad, or frightened or calm. People with autism may struggle to recognise these emotions.

To investigate how people with autism are affected by the Thatcher Illusion, scientists scanned the oxygen levels in the brains of 20 people with autism. These 20 people were given a copy of the Thatcher illusion to look at. They were then asked to focus especially on the eyes when the faces were upright. The oxygen levels increased in cortical areas when they focused on the upside down eyes on faces the right way up. The activation of these areas suggest their involvement in face processing, including the social and emotional cues processing that is so vital for our perception of the world. The activation of these areas was found to be increased in those with autism when compared to normal people.

The Thatcher Illusion gives lot of clues to why autistic people struggle to interact with other people. We think that they may struggle to prioritise information coming from peoples eyes and mouths. If this is true, we may be able to help them improve their social skills by helping them learn to focus specifically on these social and emotional cues through behavioural therapy.

The Risky Part: what to be aware of and how to keep the science safe:

Experiment | Hazard | Risk to Audience | Risk to Presenter | Control Measures | Residual Risk to Audience | Residual Risk to Presenter |

Thatcher Effect | None | None | None | NA | NA | NA |

References

It's all in the eyes: subcortical and cortical activation during grotesqueness perception in autism, PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054313.

How the Thatcher illusion reveals evolutionary differences in the face processing of primates, Anim Cogn. 2013 Feb 19

Margaret Thatcher: a new illusion, Perception. 1980;9(4):483-4.

Comments

very nice good.

very nice good.

Add a comment