How are memories formed and lost? Is Alzheimer's just an extreme version of normal ageing? And to what extent does genetics play a role? Can we protect ourselves from developing the disease? We get our head around the disease with Alzheimer's Research UK.

In this episode

00:00 - Meeting an extreme marathon knitter

Meeting an extreme marathon knitter

with Susie Hewer, Extreme Knitter

Susie Hewer holds the Guinness World record for extreme knitting, and fundraises for Alzheimers after seeing how it affected her mother.

Susie Hewer holds the Guinness World record for extreme knitting, and fundraises for Alzheimers after seeing how it affected her mother.

Hannah - Hello. I'm Hannah Critchlow and you're listening to Naked Neuroscience. This month, we're reporting from the Alzheimer's Research UK 2014 Conference in Oxford.

Alzheimer's is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that's part of a cluster of diseases called dementia. Those affected suffer from memory loss, confusion, mood changes, and difficulty with day to day tasks.

It's estimated that 1 in 3 people in the UK over the age of 65 will die with dementia, and 2/3 of these will have Alzheimer's specifically.

Alzheimer's is caused when two abnormal proteins accumulate in the brain called amyloid and tau. They form clumps called plaques and tangles that interfere with how the brain cells work. The plaques often appear first in the area of the brain that makes new memories.

To find out more about how these plaques and tangles in the brain, affect people day to day, I firstly met Susie Hewer who features in the Guinness World Book of records for her extreme knitting. She's constructed over 26 miles of scarfs while simultaneously running the London marathon. Why did she do this? Well, to raise awareness and fun for Alzheimer's Research UK. She's prompted to do this after seeing first-hand how it affected her mother's life as she explains...

Susie - She started to get quite depressed. She was very withdrawn and then the next phase was, she started to have wandering incidents. Because she lived with us and my husband worked at home, it hadn't been really a problem until then but one day, he came downstairs, he found her sitting outside in the steps because she didn't know where she was. She said, "Well, I couldn't get in." He said, "Well, why didn't you ring the doorbell?" And she hadn't thought about that.

The next thing that sort of changed our lives dramatically was, I left her in the library while she chose a book. I went over the road to the cashpoint and came back again. 5 minutes later, she wasn't there. So, I looked up and down the road, couldn't see her, went running one way and thankfully, I found her walking really fast with her head down. I said, "Mom, what's going on?" She said, "Well, you moved the car. I didn't know where you were, so I'm heading for home." She was heading completely in the wrong direction and the car was actually outside. So, at that point, we realised that the wandering could become a problem so I left my job to care for her full time. For a while, it was sort of alright because we could go out together and we both shared a love of nature and we go out together. She still help me around the house. She'd cook food sometimes although little by little, these things disappeared from her. She stopped being able to boil the kettle. She didn't know where the kettle was. And then we started to enter the really unpleasant phase. She'd walk into a room and she wouldn't sit somewhere because there was a woman there. She also had children hiding in her wardrobe stealing her clothes. She didn't sleep at night at all. She slept for about 30 minutes and then she'd get up. I'd hear her moving around and I'd get up and put her back to bed again. Then she became doubly incontinent and it's so humiliating for the person. But thankfully, by that stage, she was sort of beyond knowing what was going on.

Hannah - So, how long did it take for the doctors to finally realise that it was Alzheimer's and then start getting some kind of treatment for it?

Susie - It was about 7 years before she had a proper diagnosis. We were sent to the specialist and he took one look and he used all the questions like, what day of the week it is, who's the prime minister, which floor we were, and she got every single one of them wrong. What I found really interesting from that was that she introduced me as her cousin and she started calling my husband Mark, by that time, his name was Mike.

Hannah - And you're very active now, with both your running and also your work with Alzheimer's Research UK. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

Susie - When mum went into nursing home, we decided to find out more about Alzheimer's and I discovered Alzheimer's was vastly underfunded. I got in touch with Alzheimer's Research UK and I decided I would run a marathon to try and raise money for them. It sort of spiralled on from there and here I am 9 years later and 31 marathons under my belt, and a couple of Guinness World Records and I'm still talking about it. People ask me why am I still doing it. It's because although we talk about a little bit more, there's still this awful stigma attached to it. It's an old person with a mental illness wherein rather the way we did about cancer, we'd refer to as a big C 30 years ago.

What I'd really like is that people will speak openly about it and not be ashamed of it. And the other thing, it's still vastly underfunded. Even though the fund is made, measures to ensure that more funding is coming in, we still need more, and so, I still have to keep running.

Hannah - Thanks to Susie Hewer and you can find out about her next extreme knitting run by checking out the website, extremeknittingredhead.blogspot.com.

05:01 - A brainy panel tackle your questions

A brainy panel tackle your questions

with John Gallacher, epidemiologist from Cardiff University, Karen Ritchie, psychologist from the French National Institute of Medical Research and Kevin Morgan, geneticist from Nottingham University

How are memories formed and lost? Is Alzheimer's just an extreme version of normal aging? And to what extent does genetics play a role? Can we protect ourselves from developing the disease? We get our head around your questions...

How are memories formed and lost? Is Alzheimer's just an extreme version of normal aging? And to what extent does genetics play a role? Can we protect ourselves from developing the disease? We get our head around your questions...

We've accrued a brainy panel of experts, bringing together a geneticist, a psychologist, and an epidemiologist - so, someone who studies genes and behaviours in society.

Starting with Pekka Olinka, she got in touch asking, "How does memory work in the first place and how does it go wrong in Alzheimer's?"

John - Okay, my name is John Gallacher. I'm an epidemiologist. You could try and answer this at different levels, but just to keep you fairly straightforward, our memory works by the brain making new connections as it learns new material. These memories, these connections, are then retrieved for different purposes. Now, if those memories are wiped because the brain is mashed for dementia or for any other reason, of course, there's nothing there to retrieve. The other side of that coin is, if you are having trouble encoding or making new connections in the brain, obviously, there is less material there which has been coded or remembered in order to retrieve in the first place.

Karen - Karen Ritchie, I'm a neuropsychologist and an epidemiologist. What one needs to understand is that the learning takes place at two levels, at least, and there is a level at which we take in a certain amount of material and we analyse it and then we store it. If it is stored into a longer store and quite often, what we see with Alzheimer's disease is this inability to be able to store in the short term and to analyse, and therefore, pass it into longer term memory.

Hannah - So, just going back to these connections between brain cells and their involvement in memory, you do actually see a decrease in post mortem samples of patients with Alzheimer's in these connections?

John - Yes, in the various dementing processes, it's essentially a process of neuronal death. Therefore, the number of cell is reduced, the number of connections reduce, and therefore, the functionality of the brain reduces.

Karen - And I think we can afford to lose quite a lot of brain cells. I think one of the most important thing is not how much we lose, but exactly where we're losing them from. There are crucial parts in the brain - we talk about the hippocampus which is very much involved in learning, where cell death in those areas are going to have far more impact than in some other areas.

Kevin - I'm Kevin Morgan, University of Nottingham. I'm a human geneticist. I think what the others have referred to is the neuronal reserve hypothesis which I think is a very plausible explanation. You can think of your brain as an organ or a tissue, sort of use it or lose it. So, the more connections you can make, the more you can afford to potentially lose down the line. So, I think it's good to keep sort of exercising your brain doing puzzles, read and it certainly can't do any harm and makes life a bit more interesting as well.

Hannah - Certainly does and we'll be talking later on about things that we can do to help protect our brain against Alzheimer's. But also, It Gran has been in touch via Twitter saying, "How do you distinguish between normal old age loss of memory and Alzheimer's when diagnosing?" We all really tend to associate memory loss with getting older, but at what point does that become Alzheimer's or dementia? What's the difference? Is there a difference?

Karen - There are differences. I think firstly, that we have problems with memory at all ages. But I think as we get older, we start to become more and more sensitive about them. But I think there are some particular types of learning that we tend to lose.

We often test people using something like word lists because it tries to capture this first phase of memory where we try to take in information and organise it in order to be able to store it. Sometimes we find that this specific capacity has been lost. But the person still has intact ability to recall things that occurred quite some time ago. There's some evidence to suggest that the parts of the brain that are the first really to be hit, parts of the brain that are very much involved in visuospatial memory - that is the learning of the spatial location of things. This seems to be far more specific to Alzheimer's disease than into normal ageing.

John - You have different effects, different decrements with different sorts of dementia. So, we've talked about Alzheimer's disease particularly, but if you have vascular dementia, you'd have a different set of symptoms. Now, the difference, you could argue between a particular disease and normal ageing, maybe one just a degree. I mean, that the brain is responding to insults and challenges all the time. And over time, it's robustness to adapt will change and then maybe will be for different functions and critical moments where actually the decline drops rather rapidly and at which point, we will become symptomatic for dementia.

Kevin - I think it's important to remember that the clue is in the name Alzheimer's disease, it is a disease and I think if you go back perhaps 4 or 5 years ago, one of the big areas that was debated was the fact that if we all lived long enough, we'd all get Alzheimer's disease if it was a normal part of the ageing process. I think you just look around and see the people in their 90s or even over 100 years old that are cognitively as sharp as a button. So, it doesn't necessarily have to happen. So, there are mechanisms that kick in and as John said, there will be some individuals that are more vulnerable to those insults. But I think it's important that people realise that the normal ageing process and neurodegeneration are two distinct entities.

Karen - I think there's a whole question of what is normal. We used to think for example that cardiac capacity reduce across time with ageing. We now know that that's not the case once you take into account disease processes. Just as we've always said, it's normal to lose your memory, it's normal to have word-finding difficulties with age. I think particularly, a baby boomer era is less and less tolerant of being told that this is normal for age and is actually looking some way to rectify this.

Hannah - Thank you. Gerald McMullen has got in touch saying, "What's the role of genetics in developing Alzheimer's or dementia down the line?" Could there be a genetic test in the future that he could use to screen himself for?

Kevin - Good question. I think currently, it's a little bit premature to talk about people going for a genetic test. I think familial AD which is the rare inherited forms, they come for 2%, maybe 5% at most of Alzheimer's disease. These are the forms that the age of onset is very young, 40s and 50s - the genes are known. So, if there's a familial history, it would make sense in being screened for those particular genes.

Now, the genes involved in later onset or the sporadic form which is the remaining 95%, we're only just beginning to get a handle on what those genes are. It's debatable how big a role those genes play and we certainly haven't found them all.

So, whilst we can test for all of those genes now, it's a simple matter of doing the genotyping which is not a problem. The reality of it is, is you would be testing when you didn't have a full picture of what you wanted to test. So, you'll be covering perhaps only 20%, 25% of the known causes.

Once we've got a full understanding of all the genes involved, then these tests are likely to become a reality. It will depend on individuals deciding whether they want to know and society will dictate whether a genetic test has some meaning when currently, the treatments are running sort of decades behind the scientific findings.

Karen - I think there are also ethical issues about doing genetic screening when there isn't an efficient treatment that is behind it. We already have seen that when the first strong candidate gene apoE was discovered that for those of us who conducted community research, there was often pressure on us to reveal the apoE status to families, and perhaps even more alarming to people who were responsible for care institutions. They wanted to be able to exclude people with apoE from entering to institutions because they were very likely to develop Alzheimer's disease. So, I think there are more issues than just being able to screen genetically.

Hannah - What about the role of environmental factors? Are there particular lifestyle choices that we can make that will help protect us against developing Alzheimer's down the line?

John - I think there are. The question isn't, are there lifestyle choices we can make. It's much more, what will the impact be. All the evidence points to a fairly substantial reduction in risk for vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease by taking more exercise, having what you might call a healthy diet, fruit and vegetables, low saturated fats, and fatty fish, reducing our weight, non-excessive alcohol consumption, and non-smoking. So, these things add up together.

Karen - I think we're also limited by the fact we know very little about environmental factors. The only environmental factors we really looked at are those that occur in old age because our studies are conducted in old age. That's where the cases are. It's not necessarily where the risk exposure is, that in fact, we could be exposed to many risks much earlier in life. Perhaps even in utero that might have an impact later on and could be potentially reversible factors.

Kevin - I think the reality is, we can debate about the role of environmental factors, but the bottom line is that things that will stop you getting strokes and heart attacks, we should all really be embracing those. If there's a benefit in preventing dementia then we should all be sort of be plugging into that. I'm willing to risk the fact that these things might be doing some good as well as stopping high blood pressure and heart attacks can potentially the risk for dementia as well.

Hannah - And final question now, John Haze has been in touch saying, "What kind of treatments are available for Alzheimer's and will we even come up with a cure?"

Kevin - It's a good question. Personally speaking, my understanding of memory process and the fact that what you're doing is destroying neuronal connections that you've built up throughout your life is that finding a cure or finding treatment that can reverse that process is very daunting task indeed. I think what's more realistic is that drugs can be developed that slow the process down.

Hannah - Thanks to John Gallacher, epidemiologist from Cardiff University, Karen Ritchie, psychologist from the French National Institute of Medical Research, and Kevin Morgan, geneticist from Nottingham. This is me, Hannah Critchlow reporting from the Alzheimer's Research UK Conference for this special Naked Neuroscience episode sponsored by Alzheimer's Research UK.

15:50 - Beating Alzheimers one step at a time

Beating Alzheimers one step at a time

with Dr Eric Karran, Alzheimer’s Research UK.

Worryingly, 1 in 3 people in the UK over the age 65 will die with dementia, including with varients of it including Alzheimer 's disease. So the government and charitable funding bodies, have, over the last decade, identified this area as a major research strategic priority and pumped large amounts of cash being injected into research into the area.

Worryingly, 1 in 3 people in the UK over the age 65 will die with dementia, including with varients of it including Alzheimer 's disease. So the government and charitable funding bodies, have, over the last decade, identified this area as a major research strategic priority and pumped large amounts of cash being injected into research into the area.

So, why in that case, is diagnosis still so difficult? And why are the treatments currently on offer for Alzheimer's so inadequate?

Eric - I'm Eric Karran. I'm Director of Research, Alzheimer's Research UK.

Let's start with diagnosis. So unfortunately, the brain is a kind of an isolated organ and it's behind bone, it's in the skull, compared to other organs like liver and heart, measuring its activity is actually quite challenging.

Some of the clinical instruments that we currently use, the ways we have of assessing cognition and memory and learning are actually relatively crude still. So, we're in a situation where it's quite difficult to measure subtle changes in cognitive function even though those changes themselves may herald the development of the disease.

So, to make an analogy, if you have slightly high blood pressure, so rather than 120, it's 125 or 130, you can actually measure that very, very accurately and very, very easily. You just put a cuff around your arm and you can measure that. There's absolutely nothing comparable to that for measuring brain function at the moment. So, we're in a situation where we still have relatively imprecise and crude tools with which to try and measure and diagnose brain function.

I think the other issue is that different pathologies, different things going on in your brain can result in similar symptoms initially. And so, there is significant overlap in some cases between the pathology of one disease such as frontal temporal lobe dementia and another disease such as Parkinson's disease. And yet, the therapies for those are going to be radically different.

So, we're in a situation where we don't have good instruments to measure brain function. We don't have good diagnostic tests to know that person A has Alzheimer's disease versus another brain disease. When you put that together, you end up with an incredibly challenging problem.

I think the other issue is that these diseases, although they're very aggressive, the day to day or week to week change in cognition is actually relatively modest. And so, in terms of trying to do a drug trial to work out if a medicine is working or not, you need to continue those trials for up to 1 ½ in 2 years at a minimum. And so then you're in a position where you have people that you're not absolutely certain have the disease because of the issues of diagnosis. You have to treat them for a very long time. And then at the end of it, you have relatively imprecise tools to measure whether or not your drug is working. And so, this I think explains to a large extent why we have struggled currently to find very effective therapies.

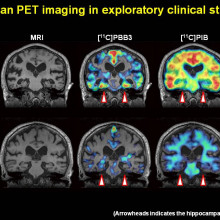

I think that's changing. We now have far better tools that can enable you to image the pathology of some of the diseases in living people without using invasive technology - so this is going in for brain scans. And so, with these new instruments, firstly, we're going to be able to select people with better accuracy for particular drug trials. So, we know that they've got the disease or the pathology that we hope to treat. And also, we'll be able to measure the effects of the drugs objectively by looking at the spread or the inhibition of spread of pathology.

And so, I'm very hopeful that we've had a decade of failure in this area, but with that failure comes learning as well. What we understand that the pharmaceutical industries had a tough time trying to develop drugs that's usually expensive. Unfortunately, some of them are withdrawing from this area to other areas where they can get a return on investment.

Hannah - So, they're moving away from the brain because it is still such an enigma. As you said, we don't have the tools for diagnosis in some disorders?

Eric - Yes. And so, if you look at where the market for drugs is growing, in other words, where countries are reimbursing the pharmaceutical industry with novel drugs, it's really in cancer, in arthritis, and in diabetes - those big three.

They are unfortunately retreating from really tough areas such as Alzheimer's disease. Not all of them. Some are staying in the course, but many of them are having to close that down. And you can understand that because they need to get a return on investment. Unless they do that, they don't research anything. So, that's a natural response.

So, what we see as being important in terms of charities if you like, trying to fill that gap, that translational gap. So previously, academics would do very novel research and the pharmaceutical industry would take a look at that research and say, "Of that research, what is it we think are going to provide promising targets for drugs ultimately?" The pharmaceutical industry is not going to be doing so much of that anymore. So, it's going to be up to academics and other groupings to be able to take up that challenge. And so, we're in a consortium where we'll be able to put money and to help those very early stage of discovery projects. I think the other really exciting thing we're doing is, we'll be paying for drug discovery institute that will be housed within an academic institution. So, this is really working very closely with academics to try and fashion their innovation and make it appropriate and right for patient benefit.

Hannah - Do we know enough about the biology of Alzheimer's in order to start developing new drugs that can treat it?

Eric - That's a good question. I mean, you never know enough about a disease, but if I contrast what we know about Alzheimer's disease, where there's a pathology we understand, there are genetic risk factors we understand, if you contrast that Schizophrenia where it's incredibly mysterious what's going on there, I think we could always do with more knowledge, but I think we do have sufficient information to come up with new targets.

Hannah - And so, how will these new drugs contrast with the current made of action of Alzheimer's drugs?

Eric - The current drugs we have are what we call symptomatic. So, they do something for some of the symptoms, but they're not particularly effective and their efficacy actually wears off pretty quickly with time. The new drugs that we'll be able to look at are really either to try and prevent, or slow down, the spread of two of the major pathological proteins in the brain. One is called A-beta, the other is called tau.

I think in the future, there's a lot of research going into tau pathology and there are some very promising drugs coming forward which seem to be able to prevent the spread of that pathology through the brain. Certainly, in animal systems, they do that. The spread of that pathology in human disease correlates very well with the loss of brain cells, and also, with the onset of dementia. So, I think that is going to be a really promising area in the future to look at.

Hannah - Thanks to Eric Karran at Alzheimer's Research UK.

23:17 - New biomarkers for Alzheimers?

New biomarkers for Alzheimers?

with Professor Simon Lovestone

Are there any better diagnostic tests, or biomarkers, that could help with early diagnosis of Alzheimer's and prevent tau tangles accumulating. Simon Lovestone is based at Oxford University...

Simon - So, I work on what are called biomarkers - essentially, tests for Alzheimer's  disease. What I'm really interested in is not so much a test for Alzheimer's disease, but can we find a way of identifying people who are going to develop Alzheimer's disease.

disease. What I'm really interested in is not so much a test for Alzheimer's disease, but can we find a way of identifying people who are going to develop Alzheimer's disease.

Hannah - What's the hope in the future? What's a realistic timescale in terms of being able to diagnose and treat Alzheimer's before the proper brain damage, in effect to actually set in?

Simon - So currently today, when people come to their doctor for the first time, worried they have Alzheimer's disease, what we actually do is do some memory tests. Often, we can't tell whether somebody has got Alzheimer's disease. So, what we then do is say, "Come back and see us in 6 months or a year and if it's got worse, we'll tell you whether it's got worse due to Alzheimer's disease or not." That's a terrible 6 months or a year for patients, not knowing what's happening, waiting for the results, terrible anxiety. So even though we have no treatments today, the way we have of diagnosing Alzheimer's disease is just not adequate. Using biomarkers today, using a lumbar puncture - that's a needle into the base of the spine to get spinal fluid or using some very complicated test, neuroimaging of the brain, we can actually diagnose Alzheimer's disease quicker today, using biomarkers. I think we should start doing more of that.

Hannah - Why is it that that isn't being implemented that commonly now? Is it cost?

Simon - I don't think it's just cost that prevents us from implementing that. I think it's logistically difficult. I think it's uncomfortable, it's invasive. Some people argue, we don't need that because we don't have any treatments. I disagree with that view. But actually, it is beginning to happen. If you look outside of Britain, in much of Europe and America, it is now becoming more routine to have a spinal fluid test as part of the diagnostic workup. My prediction is, over the next few years, you'll see a lot of that beginning to happen in the UK as well.

Hannah - What's different about the spinal fluid in a patient with early stage Alzheimer's compared to a healthy control?

Simon - So, in Alzheimer's disease, even in the early stage, you can see molecular markers that are indicative of the changes in the brain. So specifically, you see decreased amount of a protein called A-beta or amyloid. The reason why it's decreased because it's increased in the brain so there's less of it circulating around. And you see increased amounts of a protein called tau - phospho tau. The reason why that's increased is because it's a pathological change that happens in the brain of Alzheimer's disease. As the neurons die or the brain cells die, it gets released in the spinal fluid.

Hannah - What type of tests do you think we might have in the future, maybe some less invasive test than a lumbar punch?

Simon - What we know is that for 10 or 20 years before there are symptoms, there is an accumulation of pathology in the brain. So, the condition is starting even before there are any clinical symptoms at all. If only we could treat those people then we might be able to prevent the condition. At the moment, we can't treat those people because we don't have the drugs but also, we don't know who those people are. So, we're trying to develop a test that would enable us to pick up those people before they have symptoms by looking at their blood.

Hannah - What are you picking up in your blood screening studies so far?

Simon - So, we've used a method called proteomics. So, we've been looking at proteins in the blood and we start by looking at a thousand or more proteins. Over the past 10 years, we've honed down to about 10 or so. Broadly speaking, these are proteins that have something to do with immunity and the reaction of the body to stress. That makes sense because we know that the brain is under stress. We know it has an immune response. What we're finding is that immune response somehow crosses from what's happening in the brain through to something we can see in the blood.

Hannah - So, it's almost as though the Alzheimer brain is being attacked by its own immune system. It's underfire by its own soldiers almost in its defence system and that's what's causing these problems with memory and also delusions and hallucinations 20 years down the line - an attack on our own brain?

Simon - So, I think that is right. I think what happens in Alzheimer's disease is that you have a central process if you like, that's the motorway, driving the process of Alzheimer's disease. We have lots of roads feeding into that, that contribute to that process. The immune reaction of the brain is one such of those roads that is helping to drive the process along.

Hannah - How sensitive or selective are your blood diagnostic tests at the moment? Are you getting some quite promising result?

Simon - Yes, it's looking very promising indeed.

Hannah - So, if you took my blood sample now, with what percentage accuracy would you be able to predict that I would be developing Alzheimer's in 20 plus years?

Simon - Nearly zero because you're way too young. So, what we're really interested in doing is, can we take somebody who is perhaps 60 or 70 and perhaps has some memory problems already, maybe they have mild cognitive impairment. What you really want to know is what's going to happen in the next year or two. That's how we've been designing our studies. So, we know that our test is quite accurate in detecting people with mild cognitive impairment and predicting what's going to happen to them in the next 18 months.

Hannah - Promising research. Thanks to Simon Lovestone from Oxford University. Well, I'm afraid that's all we have time for this month.

Thanks to Alzheimer's Research UK for this special podcast, reporting from their conference and featuring Susie Hewer, John Gallagher, Karen Richie, Kevin Morgan, Eric Karran, and Simon Lovestone. To find out more about the disease, please visit the website worldwideweb.alzheimersresearchuk.org.

We'll be back again next month to open our minds. The topic for the next show is autistic spectrum disorder. Could environmental pollutants play a role? Is it simply extreme male behaviours? Can you diagnose newly born babies and start treating? We'll find out. If you have any comments or questions, please contact Hannah@thenakedscientists.com, you can also tweet @nakedscientists, or you can post on the Naked Scientists Facebook page. You can find the full transcript for this episode and others on our website. It's thenakedscientists.com/neuroscience. See you next month to open our minds.

- Previous Huntingtons Disease

- Next Naked at 702

Comments

Add a comment