Touring the brain by visiting a laughter clinic, the sauna and psychadelic goats, plus neuroscience nuggets from Prof Nutt!

In this episode

00:00 - Prof Nutt's Nuggets! Part One.

Prof Nutt's Nuggets! Part One.

with Professor David Nutt, Imperial College London

Hannah - Before launching into the Naked Neuroscience tour for 2013, let's kick off the programme by catching up with Psychiatrist and Pharmacologist Professor David Nutt from Imperial College London to find out his top neuroscience nuggets for the year, starting with number 5.

David - The festival of neuroscience, that I helped to coordinate hosted by the British Neuroscience Association. It's the first time we've ever done it. Fantastic display of British and international neuroscience. A wonderful series of scientific posters, symposia and of course, in parallel, truly stunning public engagement process which attracted even more people in the festival put on by the Wellcome Trust. So, that was a truly memorable period of 4 days in London in April.

The second thing I would say is rather different. This year, I've seen a very unique discovery in relation to the treatment of addiction. A drug called normorphine has been licensed to help people cut down their drinking. It's the first drinking modulator that's ever been put on the market. This is very thrilling for me because it changes the whole paradigm in how we consider treating people who drink too much. We all know people that don't want to be alcoholic, don't want to drink too much but lose control. This drug helps them (we think) gain control. So, this is a truly radical innovation. It sets quite interesting challenges to neuroscientists to work out whether - how it's working. Does it actually improve self-control? Does it reduce reinforcement in craving? That's not understood yet, but it is first of its class and it could be very, very advantageous to millions of people worldwide who would like to stop drink binging but they can't pull it together when they start.

Hannah - Thanks to you David Nutt.

04:02 - Visiting a Laughter Clinic

Visiting a Laughter Clinic

with Miss Zoe Harris, Yoga Laughter Clinic

Quite a few of you got in touch, asking about fake versus real laughter and the contagious power of giggles. In order to investigate this, I visited a yogic laughter clinic, hosted under a chestnut tree on a lush green in Cambridge. I spoke with Zoe Harris who hosts the sessions to find out why clinics like these are proving so popular.

Zoe - So, laughter yoga was invented by Dr. Madan Kataria in 1995 in India. His philosophy behind it was, as a medical doctor, he wanted his patients to improve psychologically, but without the use of drugs. So, he found an article about how laughter, even fake laughter could trick the brain into feeling more happy. And so, he researched this a bit and he started trying to get this group together in the park and they met and they told jokes to each other, and they had a bit of fun for a few weeks then the tricks got out of hand, got a bit inappropriate. And so, he developed a series of exercises that would just help promote laughter. And so, even if you don't feel like laughing, you join in and the brain will follow eventually and you release all the happy hormones, all the endorphins that oxygenate the blood and it just helps you feel very positive and enlightened person. And so, his wife was a yoga instructor and so, that's where the yogic part comes in because he combines the laughter with pranayama - so, breath of life. Some deep breathing exercises to also calm the mind as well as oxygenating the body as well. So today, we'll just be doing a series of exercises. So, no previous experience required. Just follow what we do.

Hannah - And Zoe started the clinic by asking us to laugh loudly from the belly to the skies. Here's what happened. [laughter].

We were asked to laugh at all four points in the compass and by the time we'd reach the west, it was like a pack of hyenas had hit the park.

You might be able to pick out my cackling contagiously and uncontrollably amongst the crowd. [laughter].

Worryingly, it also sounds a little bit like wailing. [laughter]

Why is laughter contagious?

We posed this question to neuroscientist Dr Tristan Bekinschtein who works with the Medical Research Council Cognition Sciences Unit, Cambridge. Tristan - Laughter, you can think of it same as yawning. So, if you start to fake yawn, you would start to yawn for real, and you will be contagious either with a fake yawn or with a real yawn. Laughter probably works the same way. So, there are a couple of papers over the last 2 years, looking at fake laughter versus some sort of real laughter. I would say, mainly, it's about smiling and they do seem to recruit quite other similar network including the motor cortex and some other areas.

Hannah - So, the motor cortex is involved in controlling our muscles.

Tristan - Yes. So, the motor cortex, it's controlling the muscles of the face and the muscles of the larynx, and the muscles you would use for to laugh. But very strong laughter does involve whole body movements in general.

Hannah - Thank you, Dr. Tristan Bekinschtein from Cambridge. A study published in 1988 by Strack and colleagues indicates that simply gripping a pencil in your mouth to induce a fake smile can make you actually find things funnier. Participants with a pencil stuck between their mouth rated cartoon images as more entertaining that those with closed lips. You can try it on the move even if you don't have a pencil on you, simply by repeating "eeee".

Does laughing alter your brain chemistry?

We put this question to Professor Sophie Scott from University College London.

Sophie - You absolutely do. So, it's been shown by Prof Robin Dunbar over in Oxford that you increase your endorphins when you laugh. That seems to be, whether or not you're really laughing or you're pose laughing. That's probably because of the physical work that you're having to do to laugh. You're doing exercise, and doesn't feel like it, but you're intercostals muscles which move when you're laughing move so much more than they do when you're normally moving: like breathing or talking. That is a bit like sort of sprinting for your rib cage. Well, like sprinting with your legs, laughing with your rib cage. So, you get the same kick from your increased uptake of endorphins that you would get from doing any other kind of exercise. There's nothing particularly special about laughter in that respect. It's a sort of exercise you can do sitting down with friends, which isn't normally the place that you do a lot of exercise. You're getting a good feeling from it via that route. Again, Robin Dunbar has shown that you get raised pain threshold when you've been laughing. The consequences they think is endorphins physically makes you better able to tolerate pain.

Hannah - Fabulous! The power of laughter makes you less susceptible to pain, releasing endorphins, exercising your body, and engaging your social brain. Thanks to Professor Sophie Scott from the University College London and Dr. Tristan Bekinschtein from Cambridge.

10:05 - Prof Nutt's Nuggets! Part Two.

Prof Nutt's Nuggets! Part Two.

with Professor David Nutt, Imperial College London

We next return to Professor Nutt for his top neuroscience nuggets for 2013.

David - Third thing is also another medication which is a drug called vortioxetine and this is the first new antidepressant in the last decade. It's a new kind of antidepressant. It's got some serotonin reuptake inhibiting properties, but it's also engineered in the molecule a very significant number of receptor interactions. It's 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist, runs on a 5-HT1D receptor as well. This is a really molecule because it does seem, as well as being an antidepressant, also have some particular ability to improve cognitive function such as poor retention and concentration in depression which is a symptom in depression that hadn't really being particularly helped by other antidepressants. So, to my mind, this is exciting and also, it is great to know that there is still innovation in the field of depression which is as many of you will probably realise, the largest cause of disability in the western world now.

Hannah - Thanks to David Nutt.

17:58 - What is it like to live with addiction?

What is it like to live with addiction?

with Toby Peters, Squeaky Gate

We now know some of the science of addiction, but what is it like to live with it? I spoke with Toby Peters who works with the music charity Squeaky Gate.

Toby - I think mental illness is much on the streets as it is behind closed doors. I think it doesn't hide prisoners basically and some people self-medicate with drugs and alcohol and when they get sober or clean, quite commonly people get diagnosed either depression or bipolar, or Schizophrenia.

Hannah - Can you tell us a little bit about your experiences?

Toby - I'm a recovering alcoholic. I've been dry and clean now for nearly 6 years, this October actually. I lived on the streets on and off for about 10 years and I always felt that I was outside looking in. I always felt that I was different. My thought patterns were different from other people. I felt like a hermit in a crowd. And alcohol basically made me comfortable for the period that it affected me until it ran out. And then it wasn't so comfortable and I sobered up and I realised that - I mean, what Squeaky Gate does really and some are a great believer that creativity, for some reason, it helps people to connect to other people. I mean, I know people who are complete outcasts, they beg on the streets, people cross the road if they're sitting on the street, they're complete social outcasts. The sort of work I do is where people can use their artistic skills or their creativity to communicate, break down barriers and people start actually listening to people with these stereotypical labels. People get acceptance and they listen. And then that sympathise in a sense of patronisation. They sort of think, "Hang on a minute. I've got a daughter or a son or I've got a mother or a father who's also suffered from mental illness." So, it's sort of like, it's not such as a taboo.

Hannah - And do you think that Squeaky Gate are providing a way of bringing people together to feel comfortable and to feel part of a team, but this time, a creative team that's creating music?

Toby - Yeah, I think it's a really good way of communities spirit (song).

It's a laugh. It's fun and I think what's really important is, it breaks down barriers for the outside world as such, to come in and see what people are doing, and we celebrating that the fact is we're not intimidated by labels. Take us what you see and I think that's really important. It's very empowering. I am a recovering alcoholic and I will be for the rest of my life. Whatever caused me to drink myself nearly to death is irrelevant now. What's relevant is the fact that I choose not to drink. I found people who support me and understand me, and give me encouragement. And mostly, these are people who have either experienced mental health or they experienced alcoholism or addiction, and it gives a way of people to communicate to each other.

Why do only some people get addicted?

We posed Layne's question to Dr Amy Milton at Cambridge University. Amy - Many people use drugs of abuse and never become addicted. So, alcohol is a really good example. Most people will go down to the pub, have a few drinks after work and is not ever a problem for them. But there are certain populations of people, people who have vulnerabilities.

If you are someone who's quite anxious, you're probably not going to enjoy using some types of drugs like for instance cocaine, which makes people quite paranoid and anxious if they take a lot of it. However, you might find that drugs like alcohol help to relieve some of their anxiety and so, you will be perhaps more likely to become addicted to those drugs.

There are some vulnerabilities like in alcoholism we're very highly heritable. So for instance, if you have particular genes that mean you don't really feel the effects of a hangover, that means in the early stages of use, you can drink more because you're not having the awful hangovers afterwards and that escalation in use then makes you more likely to become addicted.

Hannah - Thanks, Amy. And so, what proportion of the population suffer from problems with addiction?

Amy - It's perhaps surprisingly low for the numbers you would expect. So, of the people who abuse cocaine for instance, actually, only 20% of those individuals are classified as being addicted. It seems that the majority can actually have control over their drug use which, if you think again of the case of alcoholism, it's sort of a common sense example, most people can control their alcohol intake but there's a subpopulation of people who then find that they're not able to control their use. But obviously, because alcohol is a legal drug, more people use it in the first place which means the absolute numbers are greater than you would see for that subpopulation who become addicted to class A drugs for instance.

Why is stopping so hard?

Dr Amy Milton from Cambridge University tackles James' question......

Amy - Well, what happens in addiction is that drugs of abuse, what they're doing is having into the reward and motivational system. That exists so that you know what to do, certain things are good for you, so to promote you looking for food, to promote you looking for mates, and to make you avoid things that are bad for you. So, these are really evolutionary ancient systems. When they control behaviour, they do so in quite an unconscious way. You don't really want to be standing there, debating what you should be doing when there's a predator that's about to jump on you. However, when you have a drug of abuse doing this, these mechanisms are then diverted into drug seeking behaviour. As with all behaviours, repetition breeds habits and the thing about addiction is that these habits become compulsive, so you lose that break on behaviour.

Do other animals get addicted?

Amy - So, I don't know. I'm not an expert on goat addiction, but I did go and look this up. There's a little bit of discrepancies to whether it's goat or sheep, but there are certain populations of sheep and/or goats who will consume lichens and will grind their teeth down. Some lichens have psychoactive substances in them, so narcotics and hallucinogens for instance. So, this is sort of quite an unusual example of I guess a natural addiction occurring in animals.

You'll also see it actually in some monkeys. And monkeys that are near tourist resorts will go and steal cocktails from their guests and get drunk on those. I think there's also some incidences of elephants consuming overripe slightly fermenting fruit and becoming drunk. That's not necessarily the same as being addicted, but it's sort of a nice example of drug use in animals.

Animals do get addicted which is useful for those working in addiction because my lab for instance specialises in rodent models of addiction. And rats will use any drugs of abuse that humans will, with the exception of LSD actually, but I suspect that LSD is probably not that pleasant if you don't know what to expect from it. But all other drugs of abuse - heroin, amphetamine, cocaine, alcohol - the rats will use.

And interestingly, the population of rats that satisfy the diagnostic criteria for addiction is the same proportion as in human users. So, if you allow population of rats to use cocaine for instance, about 20% of those animals will work for that cocaine despite adverse consequences will escalate their use, will lose control over when they use. The other 80% of the animals will use it, but they can take it or leave it which is really similar to what you see in the humans.

Hannah - Thanks, Amy Milton from the Department of Psychology at Cambridge University. If you've got any burning questions about your brain and the nervous system, just email them to neuroscience@thenakedscientists.com, you can tweet us @nakedneuroscience or you can post on our Facebook page and we'll do our best to answer them for you.

26:41 - Prof Nutt's Nuggets! Part Three.

Prof Nutt's Nuggets! Part Three.

with Professor David Nutt, Imperial College London

We close the show by hearing again from Professor Nutt on his remaining top 2 neuroscience nuggets for 2013.

David - And then the fourth one is the recent Nobel Prizes for discovering neuronal transport mechanisms and vesicle production. Basically the synaptic machinery. These synapses determine how brains really work, the key element in terms of brain communication. So, credit to those American scientists who really pulled that apart.

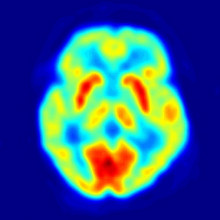

The fifth one I'm afraid is a little bit personal but I'm very proud of a study we did just published in the journal of Neuroscience which I think is the first study ever to show you could determine in a human brain the sight of action of a drug on a particular neuronal path using the fast temporal resolution of magnetoencephalography MEG, we showed that the layer 5 cortical pyramidal cells were the target of the psychedelic drug, psilocybin.

We can explain its interesting actions to produce sensory distortion and alterations in perception and hallucinations through its disruption of those neurons and the cortical microcircuit. We think that's a real world first and we hope you agree.

And the reason we're interested in psilocybin is not simply because we're interested in the psychedelic states and how that drug changes consciousness. But we're interested in why there are so many 5HT2A receptors in the brain which is the target receptor of this drug.

The layer five pyramidal cells which are the cells which essentially receive what we call top down signalling for prefrontal cortex into other parts of the cortex. Crick and Conk, but 8 years ago, thought that the layer 5 pyramidal cells with the core of consciousness. In way, we've shown them that from the first time by perturbing them with psilocybin that you were able to disrupt consciousness. So, I think we proved the Crick and Conk theory of consciousness. Psilocybin is particularly interesting drug because not only does it do that by producing a sort form disruption of that neuronal system but it also seems to - in some people to create a sense of well-being and benefit. We're in the process now of trying to develop, to explore its potentially utility as a treatment for depression because we think in depression, neural circuits gets over engaged particularly with negativeruminations. We maybe be able to disrupt that with drugs like psilocybin which is an effect psilocybin is the active ingredient in magic mushrooms. So, there's quite a lot of commentary on the web now, people are using these mushrooms to treat mental disorders such depression and obsessive compulsive disorder.

- Previous Do plants have sex?

- Next Super-shape me!

Comments

Add a comment