First known amputation uncovered in Borneo

A massive archeological find has been making headlines all over the news this week. Plus, 'breakfast like a king, dine like a pauper', is there any truth to the old saying? And are video GP consultations safe enough to be a permanent fixture in medical practice?

In this episode

00:59 - Earliest recorded human amputation

Earliest recorded human amputation

Charlotte Roberts, Durham University

The skeleton of a teenager, showing signs of the world's earliest amputation has been uncovered in a cave in Borneo. Researchers had been searching the area for cave paintings when they stumbled instead on a burial site. Archaeologist Charlotte Roberts, from Durham University, has written a commentary on the findings and gave us her reaction to what's been discovered…

Charlotte - An absolutely fascinating find. Evidence for the earliest amputation that anybody has known in a skeleton. And this is 31,000 years ago.

Chris - What have they found and where?

Charlotte - They found a 19 to 20 year old person. And this person seems to have had part of their lower leg and foot amputated. And what's more, this amputation has healed extremely well. The person survived for a number of years before they died. The office suggests that the amputation was done when this person was between 11 and 14 years old. And then the evidence of the healing suggests they lived for another six to nine years afterwards. It's quite incredible.

Chris - How do we know it was an amputation and not, for example, a wild animal?

Charlotte - Well, the cut made by whatever tool they used is very straight. And if an animal had grabbed this person's leg and ripped it off, it would have been a much more irregular break to the end of the bone.

Chris - We wouldn't have had any kind of metal instruments. They would've been using stone tools. Wouldn't they? So how on earth do you hack through bone with a stone tool?

Charlotte - Well, yes. We assume that it's a stone tool or some other thing that they found around, which could be used. It would take a long time, because obviously nowadays people use very sharp instruments to do amputations in a much more controlled environment than you would expect 31,000 years ago.

Chris - So how would they have done basic things like anaesthesia? They wouldn't have had any formal anaesthesia. Do we have any sort of documented evidence of how they might have controlled pain for what must have been an excruciating thing? If this took a long time to carve through the leg bone of an 11 year old, what would they have perhaps done?

Charlotte - Obviously we haven't got contemporary historical documents like you have more recent periods of time to tell us what sort of medicine surgery was being practiced and how they managed pain and maybe how it sedated people. But we can only assume that like today, uh, people use resources from the natural environment. Herbs that would induce anaesthesia that would manage the pain that would happen during this operation.

Chris - Do you think this was therapeutic or could it have been some kind of ritual or some other kind of tradition?

Charlotte - There are a number of reasons why you might amputate someone's limb and it could be to remove a diseased body part or an injured body part could be because of death. And today someone who has diabetes and has poor circulation may actually have to have part of their body amputated, usually their foot. But we do know from historical records that people also had amputated limbs for a punishment. So we don't really know why they did this amputation. We can only hypothesise according to what we know today.

Chris - So what do you think this tells us about how people were behaving, what they did? How does this move us forward in terms of our view of what our ancestors more than 30,000 years ago were doing and how they were conducting themselves?

Charlotte - Well, first of all, we have to remember that medicine was a key development for societies. And we assume that when people started to live in settled communities and farmed animals and plants, then they developed methods of treating ailments as time went on. But this is very, very early evidence for deliberate intervention in the form of an amputation of this person's limb. But I do think that caring is really an inherent part of being human. And to assume that people in the past didn't do these sorts of things to help their kids and kin seems ridiculous. This person was obviously looked after during their life. They survived this amputation and then they were carefully buried in a cave when they died. So I think this really shows some incredible care from the community where this person lived. So I think it really challenges the view that medicine came late in our history. It's obviously a rare find. This is a hunter gatherer society. And you think, well, if you're a hunter gatherer society, you are usually on the move. So they obviously invested in the care of this person, even though they couldn't do what they would normally do in that society. We don't know whether they were given some support, um, to walk with afterwards, an artificial limb of some sort made out again of natural resources. But I think this is an astounding find. And I think it just changes our views generally about what people could achieve in the past in terms of treatment developments.

Chris - And also presumably they must have had quite good communication as well. They must have been linguistically quite able in order to seek someone out who could help reassure this person, then perform this procedure and then rehabilitate them. That must have involved quite a lot of rich communication. So does that inform any of those aspects of our understanding?

Charlotte - Yes. You just wonder whether it was someone in their particular community or another community nearby that was willing to do this sort of operation or whether it was someone who just came forward and said, look, I'll try this and see if it works. Thinking again, in more recent periods of time in 16th, 17th century Europe, there were bone setters who went around villages, setting bones that were broken. That knowledge and skill was passed down the generations, whether that was happening all that time ago in Borneo, we'll never know, but it it's nice to reflect on that as a possibility.

07:42 - Do large breakfasts really help weight loss?

Do large breakfasts really help weight loss?

Alexandra Johnstone, University of Aberdeen

“Breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince and dine like a pauper!” has for as long as I can remember been the dietary dogma for people wanting to remain a healthy weight. The argument was that front-loading your calorie intake across the day like this benefits metabolism and makes you less likely to pile on the pounds. But is this actually true? Well, it turns out that, in metabolic terms at least, it’s wrong. Nevertheless, it might still be a valuable aid to weight control, because while this dining pattern won’t affect how many calories you burn, it might affect how much you eat in the first place. James Tytko got his teeth into the subtleties of the science with Aberdeen University’s Alexandra Johnstone…

Alexandra - Breakfast like a King, dine like a pauper is quite old fashioned. We know that what we eat influences our health, but what this study that we've published recently looks at is does, when we eat specifically impact on weight loss? Does timing of eating influence the ability for the body to mobilize and use those calories so that we can get the maximum amount of weight loss? So we have quite a specialized facility at that I worked and that we can prepare all the diets individually for our volunteers. And that really helps us achieve this type of very controlled studies where we can look at mechanistic nutrition. We had a big breakfast and a small dinner menu, and we had a small breakfast and a big dinner menu. So each subject acts as their own control. So what we're sensibly doing is comparing subjects on each of their diets. So we're not comparing subjects between each other. So within subject design. And that's really important because we are interested in appetite and appetite as a subjective sensation. What we found was that weight loss was almost identical over the four week period of each diet. And that suggests to us that actually time of day is not relevant in terms of energy metabolism.

James - Can you tell me a bit more about your subjects? Were they people who were aiming to lose weight?

Alexandra - In the study? We use an opt in approach. So yes, these are people who were extensively overweight or obese, but healthy. So it's people who are interested in taking part in our diet studies and have a commitment and time to only eat the food that we provide over a nine week period.

James - So you mentioned that on both diets, there was no change overall in their weight loss or gain. Does that mean we can consign this idea of front loading calories early in the day to old wives tale status? Is a diet that promotes eating at certain times of the day, unlikely to be effective?

Alexandra - So that's an interesting question, isn't it? Does time of day have any influence on appetite or energy balance? And actually what we found is that it does. So our main finding is that it didn't influence weight loss in terms of energy metabolism and energy expenditure, but we did find something interesting. And that was that the big breakfast regime had an impact on appetite, such that subjects reported feeling more full and less hungry when they were eating a big breakfast compared to a small breakfast. Now I think this could be really useful in what I call the real world. So it's extrapolating out our results for those people who are looking for strategies to help them lose weight. Then this could be beneficial and this will be an area for future research for us. One of the reasons that people fail to comply with a weight-loss diet is because they feel hungry. So if you start the day with our bigger breakfast, then that can potentially have an impact on behavior, because remember feeding is a form of behavior. And if you can stick to the calorie deficit over a period of time, then that type of regime could be helpful.

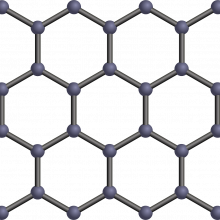

13:01 - Using graphene for rapid diagnostic tests

Using graphene for rapid diagnostic tests

Malcolm Stewart, Paragraf

A project to develop rapid diagnostic tests for infections that uses the Nobel-prizewinning substance "graphene" is underway at the Cambridgeshire-based company Paragraf. They've pioneered a way to make the carbon-based material at scale and consistently. They plan to use the technique to produce mobile-phone-sized chemical sensor devices that can pick up, in a matter of minutes, markers of disease in minute quantities of blood. Malcolm Stewart is Paragraf's Business Development Director...

Malcolm - Well, we'll take a sample of say blood, which contains lots of different biomarkers for diseases and conditions. Put it onto a Silicon chip-type device made of graphene, which is tuned to look for a particular chemical or protein or something, which tells the clinician that you've got a condition. And within a couple of minutes, from just a drop or two of blood, we can tell perhaps if you have an infection or maybe even a more serious disease.

Chris - What's special about graphene here?

Malcolm - Well, graphene is a really interesting material. A single layer of carbon atoms in a lattice shaped like honeycombs. And it's incredibly conductive and that's one of the properties that makes it ideal for diagnostics. We want to see very small quantities of these chemicals in the blood. And if you've got a very conductive material like graphene, you'll be able to see them more easily.

Chris - How do you come up with the sensors in the first place that you're gonna stick on that sheet of graphene that will find those biomarkers?

Malcolm - So what we do is we take different chemicals and join them together and at the top of that little stack is something like an antibody. And the antibody is tuned to look for a bacterium or a virus like COVID, for example, , and it, when in contact with the blood or the saliva that we put onto it, will find that protein or the virus in the sample.

Chris - And when it binds, that changes the electrical behavior of the graphene in a way that you can detect is the sort of chemical signature or electrical signature. This is bound, therefore this amount is there of that thing.

Malcolm - Yeah, exactly. So, when a binding event happens, we get a change in the electrical property, which we can measure very easily. And as that change accumulates, we can then tell how much of that chemical or biomarkers in the sample.

Chris - Now you said minute quantities. How minute are we talking about? Because in the lab that I helped to run, we are talking about a finger full of blood - big, big volumes. There's also been a company that now is somewhat infamous that made their name saying they were gonna analyze tiny quantities of blood. They went down the tubes, it was all hocus pocus. Can you really do this with tiny quantities of blood?

Malcolm - Well, we think we can. And it's about tuning the chemistry and taking the time to get all the data to show that we can. We'll do studies in real humans, in the next few years to show that we can, and we compare ourselves to devices, which are currently being used in hospitals to make sure that our performance is as good as clinicians require.

Chris - And presumably this has got lots of applications, not just in this country, but worldwide. Because if it is small, it is cheap and it's very sensitive but easy to manufacture, you could presumably roll this out to third world, many, many places with resource poor settings.

Malcolm - Very much so. And our hope is to get into helping low and medium income countries deal with simple infections, like COVID, through to much more complex tropical disease type infections, which for example, spread very rapidly. So yes, very much we have it in our sights to make sure this is a product that can be useful worldwide.

17:03 - Are health diagnoses in video calls accurate?

Are health diagnoses in video calls accurate?

Bart Demaerschalk, Mayo Clinic

Newspapers at the moment are full of letters to editors from patients disgruntled that they can't get face to face appointments with their GP. This is partly because medical consultations have moved heavily towards the use of video and telephone calls. This is partly down to Covid-19, but also is becoming increasingly common as pressed practitioners, that have seen their list sizes climb by 20% in some cases without any corresponding increase in doctor numbers, find that they can assess more patients more quickly if they use these new digital approaches. Some, particularly younger people, welcome this as more convenient. Others are less enamoured. But the crucial question must be, is it safe? Bart Demaerschalk is a neurologist and a digital care specialist at the Mayo Clinic where they've recently done a study to find out...

Bart - Our principal objective was to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the provisional diagnoses that clinicians make when they assess a patient by video telemedicine in the patient's home, compared to diagnoses established in a traditional in-person clinic evaluation. And we reason that the true scenario to test were patients presenting with a brand new clinical problem.

Chris - I guess the only way to do that then is to do a telemedicine diagnosis and then see the patient for real. And see if you change your mind, having seen them face to face versus seeing them on a Zoom call or similar

Bart - That's exactly what we did. As the World Health Organization declared the COVID 19 pandemic, and we anticipated that there would be a tremendous rise in the utilization of video telemedicine, we launched this study. This was a review of patients at Mayo clinic presenting with a new clinical problem by video telemedicine to their home, and then were subsequently seen in a traditional in person clinic environment. And the principal result was that in 87% of the patients, the provisional diagnosis following the video telemedicine consultation, matched the diagnosis established at the traditional in-person visit.

Chris - It's really interesting that you say that because, when I went to medical school, one of the first things that we were taught was more than 85% of the time, you should be able to make a diagnosis just on the basis of the history, what the patient tells you. So your numbers line up perfectly with someone else's statistics. But what that does mean is that 15% of the time it didn't. So what did you discover about those 15% of diagnoses where you had to change your mind

Bart - Precisely. So for clinical conditions that required a traditional in-person physical examination, and for those conditions where the diagnosis rested upon the result of a diagnostic study, the diagnostic accordance of the video telemedicine visit was less than the average. We also discovered that not surprisingly clinical conditions like psychiatry, psychology had high diagnostic concordance and other conditions like ear nose and throat, ophthalmology, dermatology had a lower diagnostic concordance.

Chris - Are you advocating then that maybe what we do is some kind of hybrid approach where, rather than just see everyone initially on a video call, that there are some aspects of medicine, which are really very well practiced via this sort of route, but other things we really do need to see people. And maybe we could have some kind of dichotomy there where we see face to face complaints that do look like they really do need to be seen in person, but there are some things that can vary safely be handled remotely?

Bart - That's correct. The main message is that given that this study was launched at the height of the COVID 19 pandemic, the main result is quite reassuring to our patients. The vast majority of their clinical concerns and indications they brought forward were sufficiently diagnosed by video telemedicine. But the learning yielded the fact that, for some conditions, the diagnostic concordance was high and for others low, and that this might be one of several ways in which to tailor the video telemedicine examination to those indications and clinical problems and diagnoses where it's, where it lends itself best. Over time, some clinical specialties have improved upon the video examination. For example, there are colleagues at Mayo clinic that have published their work with improving the musculoskeletal examination by video telemedicine, teaching their patients how to help the clinician over video perform a better physical examination in the absence of being able to lay hands. So this is clearly an evolving field.

Chris - Were any of the things where you had to change your diagnosis or management, subsequent to seeing the person face to face, tantamount to a clinical incident in the sense that were you not to have seen that person face to face it would've turned into a life threatening or harmful situation for that patient?

Bart - Yes, we did study morbidity and mortality. All the patients in the cohort we followed for six months after the data collection and 31 died, but in only one of those was the cause of death determined to be possibly related to a diagnostic error. So although the incidence was low, the study indicated that it's conceivable.

Chris - So what's your reading of all this then? And what would you say should be the model then based on your learning?

Bart - Almost certainly there are gonna be a multitude of digital healthcare interventions or interactions between clinicians and their patients. And we will be practicing in a hybrid model. I think in instances of primary care video, telemedicine is more likely to be successful for established patients. And for those patients that are presenting for the first time to a primary care provider with a new clinical condition, a video first approach is quite reasonable. And then escalating those cases where the clinical problem either requires a diagnostic test, a physical examination, or is in one of the categories that we've learned that has a traditionally lower diagnostic concordance to be expeditiously elevated to an in-person examination.

24:08 - Could compost fight upcoming food shortages?

Could compost fight upcoming food shortages?

Susanne Schmidt, University of Queensland

The world is tackling a shortage of food, a rising price of fertiliser, and an excess of carbon in the atmosphere. But what if there was a scheme that could help all three at the same time? Compost, the very same stuff forming in a heap at the bottom of your garden, is the centre of a new soil management scheme, dubbed the ‘precision compost strategy’, which is designed to see if compost use in large-scale agriculture could improve crop yield, soil health and divert bio waste from landfill where it generates harmful greenhouse gases. And perhaps even reduce agriculture’s reliance on mineral fertilisers as well. Susanne Schmidt, of the University of Queensland, has been speaking to Will Tingle, about how compost has been stacking up against the fertiliser competition.

Susanne - Well, the benefits really are higher yields and getting more organic carbon into soils. So we calculated that with such a global strategy we could deliver in some situations, huge benefits that in dry and warm climates soils that are acidic, or have a sandy or clay texture, that compost achieved up to 40% more yield than conventional practice using mineral fertiliser. But when we looked at it globally, so in other words all the soils and climates and crops, we estimated that designer compost would increase the production of major cereal yields by 4%, which is over 96 million tons of grain annually. And for comparison, this is about double the grain yield harvested in Australia in a good year. So it's a substantial amount. And then the other benefit is that such a strategy has the technological potential to restore about 19 billion tons of organic carbon and soil. And that is nearly a third of current top soil carbon, in the upper 20 centimetres of soil. And so we propose that compost really should become part of human's toolkit for reversing climate change.

Will - So would this new method be more cost effective than current compost management, If you can call it that?

Susanne - That's a good question, which we actually did not investigate in our study, but we can assume that some costs are reduced because less mineral fertiliser is used. But depending on how much compost is applied to fields, transport costs may be higher. And one would, however, also need to include environmental costs such as water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from conventional fertiliser versus compost, but then also consider the cost of the waste going into landfill. And we have started to address this question now using economic tools.

Will - There are some concerns that creating compost can lead to a production of nitrous oxide, which is a potent greenhouse gas. Could this method of compost management that you're proposing lead to an increased amount of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere?

Susanne - That is a really good point and that's why we included nitrous oxide emissions in our global analysis because adding organic matter to soil in the presence of nitrogen has been shown to increase nitrous oxide emissions. But we did not find evidence that compost systematically increases nitrous oxide emissions over those derived from mineral fertiliser. But we didn't have quite as much data as we had for yield and soil organic carbon and it would be good to investigate this more. But what we did see when compost was blended, it was mineral fertiliser to nourish, for example, nitrogen demanding crops, which is part of the precision compost strategy. We found that higher efficiency ensued. So in other words, compost used more of the supplied nitrogen in such organomineral fertiliser combinations. And that means that less nitrogen is wasted and lost from soil and indirectly that may mean that also less nitrogen oxide is produced.

Will - This compost management system could increase food production by 4%. I think it said, so this is something that the world sorely needs. How realistic would it be to roll out this new strategy on a worldwide scale?

Susanne - Well, as an optimistic scientist and educator, I would say that it is entirely achievable. There is now a lot of interest in transforming waste to value, as part of the circular economy. And there are many organic waste that can be used for composting. So farmers can make their own compost using farm waste and manures, city councils can use organic waste from households and green spaces, and wastewater managers have bio-solids that can be composted.

Comments

Add a comment