Frankenfoods, Formula 1 & Fake news

This week, we have an egg-cellent panel of spectacular science specialists who will be diving into their areas of expertise and sharing the goods! We hear about how formula 1 technology is changing the world, tools for coping with grief, some of the biggest controversies in science media and an update on the James Webb telescope as it preps for capturing the universe. Plus, we put our panel to the test with a science news quiz and follow clues on an easter egg trail which takes us all around the globe...

In this episode

01:20 - Meet our panel of 'egg-cellent' experts!

Meet our panel of 'egg-cellent' experts!

Mary-Frances O’Connor, University of Arizona & Kit Chapman, Falmouth University & Matt Bothwell, University of Cambridge & Fiona Fox, Science Media Centre

Julia - We have an incredible panel this week who will be hopping along with us for the next hour and sharing their knowledge nuggets on the way. First up, we have Mary-Frances O'Connor who joins us stateside today. Mary Francis is a neuroscientist who specialises in the study of grief. Mary Francis's new book, 'The Grieving Brain: The Surprising Signs of How We Learn from Love and Loss', shares the groundbreaking discoveries about what happens in our brain when we grieve and gives a different perspective on understanding love and loss. Mary Francis, what is the difference between grief and grieving and how do you study this in your lab?

Mary-Frances - Well, I think the distinction between grief and grieving is not something we use day to day. We use those words interchangeably but, if you think about it, grief is that feeling, that wave, that just overcomes you. That intense and awful feeling. But grieving is the way that feeling of grief changes over time without actually ever going away. The reason I think it's useful to make this distinction is that we will feel grief forever, whenever we become aware of something so important to us that we've lost, even if that's weeks and months and years after the death of a loved one. Just in that moment, you open a book and you see a card from your mom who's died, and of course you're going to feel grief in that moment, right. But it doesn't mean just because you feel grief then that your grieving hasn't also changed. The first hundred times you may think, "I'm not going to get through this, this wave of grief," and then the hundred and first time, it's just as awful, but it's more familiar. You know, "I am going to get through this," and maybe you even have some tools to comfort yourself, or reach out to someone else. My very favourite technique is very scientific: it's called the clinical interview, and we spend a lot of time talking with people about what their experience is like, because often their description really gives us insights into the way that the brain is working. We also use neuro-imaging scans, brain scans, where we have someone bring us a photo of the person who's died and we put that on goggles when they're in the neuro-imaging scanner, so they can look at the person. That often elicits that wave of grief for them. So we can see what neurons are being activated.

Julia - So next, coming out of the pit lane, is Kit Chapman. Kit has a background in pharmacy and science history and is an award winning science journalist who covers topics like chemistry, nuclear science, and element discovery. Kit's latest book, 'Racing Green: How Motorsport Science Can Save the World', explores how the science of motorsport goes way beyond the thrilling races which captivate audiences in their millions. Kit, what is the link between Formula 1 cars and keeping food cool?

Kit - This is the aerodynamics of Formula 1 cars. Formula 1 teams, such as Williams, actually use their aerodynamics in supermarket freezers. If you've gone to a supermarket recently, and you've gone to one of those reach-in freezers where you get your food, literally straight from the freezer, it's probably used Formula 1 aerodynamics. In a freezer, the cold air starts at the top and it flows down to the bottom and, usually, when it hits a shelving unit or someone's hand, that's going to spill out of the cabinet. That's not what you want. What you want is a nice controlled flow that moves between the shelves. It keeps the cold air in, it keeps your feet warm, and it stops using energy that would otherwise be needed to cool that cabinet. So, you also reduce carbon footprints if you can control that air. What Formula 1 teams have done is they've invented blades which literally clip onto those shelving units and keep the air flowing back into the cabinets. That saves a huge amount of energy for each individual store, and when you think about how many supermarkets there are in the world, suddenly we'll be having a massive impact on climate change.

Julia - Very cool. And that was a really bad pun for me. Onto our next panellist, Fiona Fox, who is head of The Science Media Centre. The Science Media Centre is an independent press office which gives members of the public access to scientific evidence and expertise when science hits the headlines. Fiona's new book, 'Beyond the Hype: the Inside Story of Science's Biggest Media Controversies', offers a backstage pass to the real science behind those attention grabbing headlines over the past two decades. Fiona, what is best away we can ensure a new source we're reading is legitimate when it comes to science reporting.

Fiona - I think to double check where the scientist is speaking from and ask a few questions about the article you're reading or who you're listening to: what size of study this is, at what stage is it at, is it really early results from, maybe, a pre-print that hasn't yet been published, or is it a huge, randomised, control trial that confirms the previous 10? There's a few little tips that we give to the public as to work out whether or not they should take an article they're reading as very reliable and close to the truth or very preliminary and a long way off the truth.

Julia - Finally, we have the out of this world public astronomer from the University of Cambridge, Matt Bothwell. Matt has a background in researching astrophysics, studying how galaxies evolved over cosmic time. Matt works as a science communicator, giving talks and workshops on astrophysics and has authored a book, 'The Invisible Universe: Why There's More to Reality Than Meets the Eye'. Matt, what is your favourite object in the universe that we can't see, and why?

Matt - Oh, that's a very good question. I think I might be absolutely biased and say that it's one of my hidden galaxies I used to work on. Very, very far away in the universe we can see galaxies which are sort of baby galaxies: they've just formed. We're looking at them maybe 500 million years or a billion years after the big bang, so we're looking back to when the universe was about 5% of its current age. There are these galaxies that are just the biggest firework shows in the universe, they are making stars like nothing else. We can't see them at all with our naked eye because they're so dusty and they're cocooned away so that no visible light leaks out. We had no idea that these things existed until we looked with long wavelength infrared telescopes, and then we suddenly saw the early universe lit up like a firework show. It's absolutely remarkable. It's a real testament to the power of invisible light to reveal things in the universe that we can't see.

Julia - Wow. Like New Year's Eve on steroids. Sounds like something I definitely want to see.

09:36 - Learning to live with loss

Learning to live with loss

Mary-Frances O'Connor, University of Arizona

Over the past two years, many of us have sadly experienced grief, and whether that's through the personal loss of a loved one, or the general sense of loss that the pandemic and other big world events like war have brought us, or just loss of the way life was before 2020. Mary-Frances, a grief expert, explains about this area of research to Julia Ravey...

Julia - So, Mary-Frances, your new book explains the research undertaken to understand grief. What has research taught us about how grief impacts our brains and our bodies?

Mary-Frances - I think one of the things I find most fascinating is that you can't study the neurobiology of grief without also understanding the neurobiology of love, of attachment. So, the death of a loved one, it's not just a stressful life event. Of course it is that, but it isn't just like surviving an earthquake, or being robbed. The neurobiology of grief teaches us that, first, there is the encoding of your loved one in the brain, and that is what causes the feelings of loss when a loved one dies. It means that the brain then has this representation, it has this image of a "we". Then, when the person is gone and they've died, it really is like a piece of us is gone as well, just exactly the way people describe feeling like there's a hole where the loved one should be.

Julia - Why does it take so long for our brains to come to terms with loss? Are there individual differences in how extensive this time period is?

Mary-Frances - Well, you can think about the brain as a prediction machine. Your heart is there to pump blood around your body, your brain is there to try and predict what might happen next. It does this by using all the days of lived experience that it's accumulated. Say, a woman wakes up alone in bed in the morning and her husband isn't there next to her, and he has been there for thousands and thousands of days. That first morning, it's actually not a very good prediction to assume that he's died. Rather, it takes a long time and, more importantly, a lot of experiences, for the a brain to really update, to know that this is the new state of the world for you. For that reason, I think it's very helpful to think of grieving as a form of learning. We all know learning, it takes a long time, we've been doing this our whole lives, right? It can be very frustrating, it doesn't usually take a linear direction.

Julia - I really like that, thinking of it as learning, because we've all experienced grief or we will experience grief in our lives. It's bound to be a very tough time for people, but are there tools or methods which can make this process healthier for people going through it?

Mary-Frances - The most important thing is having a big toolkit of coping skills. It really is about flexibly being able to use different coping methods depending on what the situation is that you're in at the present. For example, if your son has a football game, right, it may be perfectly appropriate to just think, "I'm not going to think about this right now, I'm just going to pretend this hasn't happened, that my loved one has died, I'm just going to cheer for my son in this game for the next 40 minutes and not think about it at all." That kind of avoidance in small doses is totally appropriate because it fits the situation. It's also really important to have someone whose shoulder you might cry on that you might try to explain how you're feeling, which is often very different than what people are expecting to feel. But also, ways to physically relax. Grieving is extremely stressful for the body as well as the mind. Things like yoga and going for a walk actually help you be more resilient through this really difficult process.

Julia - The word grieving is used outside the context of losing a loved one in our life. It also describes when we lose a job, or we break up with a romantic partner. Is this type of grief different, biologically, to when you lose someone.

Mary-Frances - In terms of evolution, a loved one is as important to our survival as food and water. For that reason, this is why we have that attachment neurobiology around this bond. The grief that is evoked when that loved one is gone is very deeply conserved. It's a loss of a part of ourselves. If you think of the word daughter, even though I'm using that to describe me, it actually describes two people, doesn't it? There's this loss of a piece of yourself, and that's similar to other kinds of losses: loss of a job, or loss of health - those are both a part of a loss of yourself. So, I think the feelings of grief piggyback on this neurobiology of grief. They have evolved around the death of our loved ones but that's, I think, why it feels so familiar.

Julia - And you use neuroscience to try and understand grief. What would be the biggest question you hope neuroscience research can help us answer about grief?

Mary-Frances - I think a lot of people want to understand, "does it matter the way we think about our loved ones, the way we think about grief." All the ways we manage those intrusive thoughts that just keep coming to us: "Does it matter how much we express our grief to other people or through art?" And so, most of our neuro-imaging studies right now are of grief of that moment, but it would take multiple brain scans across the first year or two of the same person while they're grieving to see how the brain changes over time and whether some of these expressions of grief and the way we cope with our thoughts really makes a difference as to how the brain adapts over time.

17:43 - How Formula 1 is changing the world

How Formula 1 is changing the world

Kit Chapman, Falmouth University

Let's zoom straight into our next science spotlight. The 2022 Formula 1 races are underway and while there is always a lot of drama and excitement when the race cars are flying round the track at over 200 miles per hour, it is the feats of science and engineering off the track that are impacting the world that we live in. Julia Ravey speaks to Kit Chapman...

Julia - what science goes on on the sidelines of Formula 1 racing, and how has this been used during the pandemic?

Kit - There's so much science that goes on in Formula 1. When you look at cars around the track, don't see cars racing, think about the world's fastest R and D lab, because there are thousands of engineers that put those cars on track, and they're always coming up with great ideas to make them go a second, or a 10th of a second, or even a hundredth of a second faster. Those ideas spill out into our world. In March, 2020, we were in real trouble: we didn't have enough ventilators to keep people alive. Also, we didn't want people going on ventilators because, ultimately, if someone's on a ventilator, they're on it for a month. So, UCL were looking at how they could use what's called CPAP machines, continuous positive airway pressure. Rebecca Shipley was a professor there, and she contacted another professor, Tim Baker, who had previously worked in Formula 1. He made a few phone calls and called up the engineering team at Mercedes AMG High Performance Power Trains. They produce the engines for Formula 1 cars. They sent down three engineers and, within 26 hours, they had taken apart an old CPAP machine that they'd found. They copied it and prototyped it and, in 3 days, they had that on the ward. Within 12 days, they'd actually got medical approval from the regulatory agency of the UK, not just for that device, but a device that they had actually based on it specifically for COVID patients. Within 30 days, they had produced 10,000 of them for the NHS. They had turned a factory that produced Formula 1 car engines into a medical production facility. The quality of engineering that they do, and the speed in which they can do it, is phenomenal. It saved lives during the pandemic.

Julia - And the title of your book, 'Racing Green', also indicates that some of these ingenious inventions are sustainable for the planet as well. How are some of the engineering methods of Formula 1 helping our planet?

Kit - We've got regenerative braking, which is, when you brake, the energy can be turned from the brakes and help to power a battery in your car. Also, a lot of people don't know that the first ever purpose-built racer was actually an electric car. We're also seeing use of new materials. So, for example, McLaren have actually been making their drivers' seats out of flax fibres, and using that instead of carbon fibre, which is incredibly CO2 intensive to make. We're even making tyres out of dandelions. So, instead of using rubber from traditional Amazon sources, which has now moved over to Southeast Asia in Thailand, we were actually localising them and growing tyres out of dandelion rubber, which is just astonishing to me.

Julia - Fantastic. And are there any interesting developments in the world of Formula 1 in terms of advancing technology and engineering which you think will make an exciting impact on other industries in the future?

Kit - The one that I think is really exciting is graphene. Graphene is one of those wonderful materials. It's essentially one single molecule-thick chicken wire is the best way to think of it. We were in the position that the Victorians were in: the Victorians could never imagine what plastics would actually be able to bring to society. They had no idea about how we would use plastics in our daily lives. In the same way, we have absolutely no idea how graphene is going to be used, but we're already seeing it in Formula 1. They're looking at it in lubricants, in coolant facilities, to actually use carbon to cool down engines and things like that. They're looking at the body work, in terms of the electronics, because it's a fantastic electrical conductor. They're even looking at it in crash helmets. That's actually already being used. I think graphene is the big one that's really going to just span out and we can't even comprehend the changes that it's going to bring to our lives.

Julia - Well, very excited to see where that goes in the future. And just like the Grand Prix, your work has taken you all over the world, talking about science history. As a science storyteller, what is the most important message that you like to convey when you are communicating?

Kit - You are absolutely right. I've travelled to, I think, 76 countries now. I've gone down the Amazon, I've been around Cape Horn, I've literally circumnavigated South America. The thing that I would most want people to take away from science is how interconnected it is. Just because one idea is happening in one area doesn't mean it can't spin out into another and everything impacts. We're no longer looking at this as sole scientists striving and coming up with an idea and then doing it in isolation. It's now big teams and collaborations and everything joins together. It's all about the interconnectivity of our world, and that really pushes science forward

22:53 - Tackling science media controversies

Tackling science media controversies

Fiona Fox, Science Media Centre

From one science storyteller to another, Fiona Fox, chief executive of the Science Media Centre in the UK, tell's Julia Ravey about what the Science Media Centre does, and how science media controversies need expert voices to tackle misinformation...

Fiona - We're an independent press office and we were set up around 2002. We're 20 this year and we were really in the wake of the big media controversies around GM crops, Franken-foods, MMR causing autism - as was alleged then - and animal rights extremism, as well, which was at its high point. It was felt at that time that the scientific community were just not engaging in enough numbers, or effectively enough with these big, messy, politicised controversies. So, our mission is really to improve the quality of the science that is being seen and heard by the public through the news media. We've got very narrow focus on the news media, but a very big goal, which is the wider public and their views on vaccination, climate change, animal research, etc. The way we do it is by making it easier for journalists to get access to really good quality scientists.

Julia - That's so important now as well with how fast news spreads - it's really important that it comes initially from the horse's mouth, from a great source. And your book, 'Beyond the Hype', addresses the real stories behind some of the biggest controversies in science. You mentioned a few of them there, the MMR and autism, and there was that hype about genetically modified foods, which were nicknamed Franken-foods in the media. I just wanted to know, what did this sort of coverage do for the reputation of genetically modified foods?

Fiona - It was fatal. I must say, we arrived quite far into this media fury: 2002. By the time we arrived, I can honestly say that the British public had more or less said 'no' to GM crops. When asked in surveys, they said they didn't like the idea. Supermarkets came out and started to ban anything with traces of GM in it. The supermarket said 'no.' And, eventually, the politicians, because their post bags were full of campaigners saying, 'we don't want GM.' It was absolutely fatal, and I think plant scientists then, 22-23 years ago, didn't have that track record of engaging in these big media controversies. They were coming out when they had a beautiful paper in 'Nature', but what they weren't used to, and just weren't prepared to do, really, was enter the fray and go on BBC 5 Live and Sky News with these very articulate campaigners in Friends of the Earth and GreenPeace, who were opposed to GM. It really was the case, in my view, having looked back at this and really reflected and spoken to hundreds of plant scientists, that the scientific community did not come out in numbers and speak to the public

Julia - Over the past couple of years especially, the line between science and politics has really started to blur. We've seen during the COVID-19 pandemic that governments across the world are giving out advice from experts, but then you have experts online disagreeing with this advice that's being given out. What problems does this blurring cause? And can we ever really separate politics and science?

Fiona - That's such a good question. I really try to grapple with this in my book. To me, this desire, especially in a pandemic, for a single clear public health message - and I had government press officers coming to me and saying, "we are really annoyed because the Science Media Centre is putting out all of these scientists, they're all saying contradictory things, there's multiple voices and we need one clear public health message." And this was in February 2020; there was no scientific consensus. There was no clear message. It was not understood by the best scientists in the world. We really fought against that. We really fought against this single clear messaging. It's absolutely fine for the government to do that and, of course, that was right and proper, but we didn't want to adopt the whole of the scientific community into their government messaging. So, I've been trying to champion multiple voices - as long as they're good voices, as long as they're good scientists, who stick in their lane and talk around their own expertise - that actually the more of those we hear the better, and if there is huge uncertainty, and if there are disagreements amongst scientists, let it all hang out. Actually, the public showed themselves, on the whole, to be very sophisticated in their understanding of science during this pandemic. That's what I'd like to call for: some kind of principle of a separation of scientific data being put into the public domain and then we can all argue over how we interpret that. But, at the moment, often that data is given to the government and they communicate it. That's where I think things went a bit wrong.

Julia - Yeah, I think that's really important. Especially, like you said, if there was an individual message from the start of the pandemic, things like wearing a mask wouldn't have been taken into account. So important.

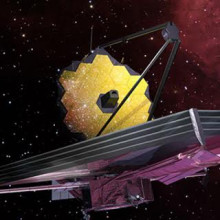

29:59 - James Webb capturing distant galaxies

James Webb capturing distant galaxies

Matt Bothwell, University of Cambridge

There's been a lot happening up in the skies recently. Matt Bothwell from the University of Cambridge brings Juia Ravey some insights on these exciting extra-terrestrial endeavours...

Julia - There's been some brilliant images circulated online of James Webb capturing loads of really bright objects. What have the images from the scope shown us so far? And when are we hoping to see those first proper images come through?

Matt - I think the most exciting thing about the incredible James Webb images we've seen so far is that we haven't actually seen any real science data yet. So far, all we've seen are the engineering calibration images. Because the mirror is 6.5 meters wide, it was too big to be sent up as a single mirror, so there's actually 18 different hexagons that all function as one big mirror. It's a marvel of engineering; this thing was launched and then unfolded in this origami-like way in space. A few months ago, the telescope focused on a bright nearby star and took the first image and it didn't look particularly great. It was 18 different, strange blurry images of the same star. Over the last few months, those mirrors have had these micro adjustments to bring them all into unanimous harmony, and so they produced one single image of one star for the first time. The most striking thing I think for me, particularly as a galaxy astronomer, is that in the background you can see just an absolute field of galaxies behind this star. James Webb is so sensitive, it can't help but pick up a swarm of galaxies every time it looks, because it's so sensitive. It can't help but see back to the start of the universe, every time it opens its eyes. The first science images should be arriving this summer.

Julia - James Webb to me sounds like that kid who doesn't even try and gets top marks in class. Just getting all those galaxies in the background and not even trying. Obviously we're gonna see the universe like never before with James Webb. Are there any problems in cosmology at the minute, which we hope that this can help us to solve?

Matt - Yeah. James Webb has a few sort of major science goals. One of them is 'what do the atmospheres of exoplanets look like?' It's going to be very good at looking for the signatures of molecules. James Webb is gonna be very good at looking very, very far away in the universe and seeing basically the first galaxies ever to form. I think the most exciting thing is almost not so much which questions will it answer, but which questions will it reveal. James Webb will look for new exciting problems that we can go and solve in the future. It's like a double whammy. It's going to be great.

Julia - All those unknown unknowns, definitely coming our way soon. Now that we're heading into the warmer months, many of us might be sitting outside on a warm night, looking up at the sky. How can we get the best stargazing experience at home? What are your top tips?

Matt - First of all, as much as you can try to go away from lights, such as lights in your house and street lights and stuff. All of that's going to be pretty bad. Get the darkest sky you can. If you are in the middle of a city, then maybe go out to a park or a field or something. It's also good to remember that your eyes take about 20 minutes or half an hour to properly adapt to the dark and looking at a phone screen will ruin your dark adoption, so make sure you spend time in the dark and let your eyes adjust, and then you'll be able to see fainter and fainter things. There are some really cool things to look out for in the summer sky. I think my favorite thing to look for is the summer triangle. It's this very striking constellation. You can't really miss it. If you look up in the summer months, you'll see this huge triangle in the sky made of these three stars. What I like about these three stars is that it hides a really remarkable secret. One of the stars is Vega, that's about 25 light years away. One of the stars is Altair and that's about 16 light years away. But one of the stars is Deneb and that is nearly 4,000 light years away and it's in fact, one of the brightest stars in the entire galaxy. It's 200,000 times more powerful than our sun. It's the most distant thing we can see with our naked eye, and it's just hiding there completely innocuously. I like pointing out that triangle to people and saying that that star there is the most distant thing you can see with your eyes.

Julia - Well, I'm definitely going to look out for that. I've moved recently from London to Cambridge and my goodness, there's a difference in looking up and seeing the stars. We're just going to move a little bit closer to home now. There have been reports over the past few months of problems with space junk. What needs to be done to keep our skies clear?

Matt - There is a lot of junk out there and space, particularly orbiting around the earth and it's getting worse and worse. There are tens of thousands of things in earth orbit. We do a few things to try and mitigate this. First of all, when we do human space flight, we make sure that we stay in orbits that are relatively clear of space junk. But long term, we are going to have to think about clearing it up. There are all kinds of solutions that are being proposed from big nets in space catching it all, to shooting it down with a laser. The issue is it's only going to get worse because when two pieces of space junk crash into each other, they often fragment and you end up with a hundred pieces of space junk and so you get this cascade. Unless we do something about it, leaving earth orbits within a few decades could be quite difficult. Clean-up efforts are needed.

Julia - Yeah, we need a space recycling centre, for sure. We need one of them up there.

35:17 - Newsworthy: Science quiz

Newsworthy: Science quiz

Mary-Frances O’Connor, University of Arizona & Kit Chapman, Falmouth University & Matt Bothwell, University of Cambridge & Fiona Fox, Science Media Centre

Julia Ravey puts our scientists to the test in a game called 'Newsworthy'. Fiona Fox and Matt Bothwell are team 1, and Mary Francis O'Connor and Kit Chapman are team 2. They'll have 3 quick questions to answer on a category based on a recent science news story and the team which answers the most questions correctly, will be crowned the champions! The 4 categories are Pigs, Wrecks, Tics, and Resurrect...

Julia - The team going first will get to pick one of those categories and to do a little coin toss, it's going to be whichever team gets the closest to the number of estimated electric cars on the roads in the UK, as of January 2022. As a team, you give me a number, whoever gets the closest gets to go first.

Kit - I should know this.

Fiona - You should know this. Yes. I think that you've got an advantage there.

Kit - Should I go first then? Because I don't know it. Electric cars on the road in the UK, I'm going say 90,000. Does that sound right? Mary-Frances, something like that?

Mary-Frances - I'm at a bit of a disadvantage, but it sounds absolutely right.

Matt - Can we do the 'Price is Right' strategy and say 90,001? That feels obnoxious. I was going to say higher - a couple of hundred thousand or something. What are your thoughts Fiona?

Fiona - Yeah, go for it. Let's go for 200,000 and shame Kit.

Julia - Well the answer is, as of January 2022, there are thought to be 400,000 electric cars on the road in the UK, which is good!

Mary-Frances - That's fantastic.

Kit - Yeah. That's much better than I thought we were doing.

Julia - And it was 720,000 hybrids, I think as well. So very, very good. That's just purely electric cars. That means Fiona and Matt, you get to go first. Your choice of topic is Pigs, Wrecks, Ticks or Resurrect. What would you like to go for first?

Matt - I drove home from school and I was admiring a field of pigs as I was driving, so that one's calling to me.

Fiona - Well I think pigs, because it's more likely to be a controversial story, like genetically modified pigs or using pigs' hearts in transplants. Yeah. Let's do pigs.

News story - [https://www.thenakedscientists.com/podcasts/short/pig-grunts-indicate-th...

Julia - Using machine learning, and over 7,000 pig sounds, a recent research study found that they could indicate if a pig was in a positive or a negative environment using their grunts alone with up to 90% accuracy. Essentially, they've designed a pig translator. In this study, short grunts with the sounds associated with pigs feeling happy, but what is a physical sign that pig are content? Is it a) when they grind their teeth, b) when they wiggle their snout, or c) when they start to sweat?

Matt - I was really hoping you were going to give us that machine learning stuff and then just say, "Is that true or false?"

Julia - It's true.

Matt - Do you have any thoughts Fiona?

Fiona - I don't. I want it to be wiggle their snouts now because that's the funniest.

Matt - I think it might be tooth grinding because I don't think sweat is under that much emotional control. I think wiggle snout is a bit too cute. I think that one's trying to bait us. Okay. Do you wanna go for teeth grinding then?

Julia - Yes, that's correct. You got one point there. It is when they grind their teeth. The next question is pigs are intelligent and sociable animals, meaning they enjoy playing with others. Pigs normally hang around in groups. What are these groups called? Is it a) a shrewdness, b) a sedge, or c) a sounder?

Fiona - I mean literally no idea.

Matt - A sounder sounds vaguely marine to me. I'm not feeling that one. Maybe sedge? I feel like a group of pigs would have an old sort of Anglo Saxon word that people have been using for a long time because people have been farming pigs. I don't think people 200 years ago would've been talking about a shrewdness of pigs, right? Sedge feels right.

Fiona - Yeah. I'm fully supportive of sedge.

Julia - The answer is c) a sounder. It is a sounder of pigs. Shrewdness is apes. Sedge, I now can't remember off the top of my head what sedge was. But yes, sounder is a group of pigs. You've got 1 point there still. The aim of this research was to improve the emotional wellbeing of pigs that live on farms. Roughly how many pigs are on farms in the UK? Is it a) 3.5 million, b) 4.7 million, or c) 5.9 million?

Fiona - I'm going to say there's loads of pigs. Should we do 5.9 million?

Matt - Yeah. Do the highest one.

Fiona - Yeah. 5.9 million. We were good on cars by going high weren't we? So yes. 5.9 million. Final answer.

Julia - The answer is 4.7 million. It was in the middle of the road. But at the end of that round, you've got 1 point. Kit and Mary-Frances, we're coming to you now. The categories we've got left are Wrecks, Tics, and Resurrect.

Kit - What do you fancy Mary-Frances?

Mary-Frances - Tic sounds the most concrete of those, I suppose. So should we say tics?

Kit - Sure. Let's 'tic' that box.

Julia - Let's tick that box. I like that a lot.

News story - [https://www.thenakedscientists.com/articles/interviews/can-social-media-...

Julia - In a recent small scale study, there was found to be a link between social media usage and an increase in the severity of tic-like behaviours in individuals. This coincides with observations that there appear to be more teenagers, particularly teenage girls, who are developing tic-like behaviors. Which of these conditions is a tic disorder? a) dravet syndrome, b) gerstmann syndrome, or c) tourette syndrome?

Mary-Frances - I know this one. Tourettes.

Julia - The answer is c) tourette syndrome. Spot on. Straight in there as well with that answer. On the social media platform TikTok, users can add hashtags to their videos to indicate what their content is about. How many videos have the hashtag "tourettes"? Is it a) 500,000, b) 5.5 million, or c) 5.5 billion?

Kit - I think it's in the millions. There aren't billions of videos on TikTok yet. So I would say just the 5 million. That sounds right to me.

Mary-Frances - That sounds right.

Julia - I've got 5.5 billion here. Now you're making me question it, but I've got c) 5.5 billion.

Kit - 5.5 billion videos!?

Julia - I'm gonna have to just look that up really quickly.

Mary-Frances - It is very popular.

Kit - It is popular, but there are only 8 billion people in the world.

Julia - Oh, sorry. 5.6 billion views. Sorry, I got the question wrong. It's how many video views has it had! That was my bad. I got the question wrong. I feel like I should give you a point for that. 5.6 billion views is still a lot. Functional conditions, those where the causes is known, have spread through populations before, including a phenomenal known as mass psychogenic illness or mass hysteria. The earliest documented cases of mass hysteria were in the middle ages. What was the main symptom of these outbreaks? Was it a) headaches, b) dancing, or c) fainting?

Kit - I know there was a series of dancing manias in Germany, in the middle ages and you do have fainting with witch trials and things like that. But I think the dancing one is quite famous. Isn't it?

Mary - Yeah. I say fainting is a close second, but I would go dancing as well.

Julia - And you are spot on. It is b) dancing. That was a full house. 3/3 Well done.

Julia - Back to Fiona and Matt now. Your choice is Wrecks or Resurrect.

Matt - I chose the last one. This one's your choice.

Fiona - Okay. Let's go for Resurrect.

News Story - [https://www.thenakedscientists.com/articles/interviews/bringing-back-woo...

Julia - A study published in current biology explored if it is possible to resurrect extinct species using molecular biology techniques in a process known as de-extinction. This includes taking DNA from a closely related relative, and altering the sequence to match the extinct animal. One molecular biology technique allows the specific editing of a DNA sequence. Is it a) electrophoresis, b) CRISPR, or c) PCR?

Fiona - CRISPR.

Matt - Yeah. CRISPR.

Julia - Spot on. Straight in there. No discussion b) CRISPR.

Fiona - That's because it's controversial. If it's controversial, I know it.

Julia - Well there you go. CRISPR is correct. That's 1 point there. In this study, the researchers were trying to recreate the Christmas Island rat, which went extinct in the early 20th century. What is the reported maximum size these rats could grow to? Is it a) half a foot, b) 1 foot, or c) 1.5 feet?

Matt - I just want to go big now.

Julia - Go big or go home?

Matt - Big rats. Half a foot is nothing, that's pitiful. I think it's gonna be either a foot or 1.5 feet.

Fiona - I agree. I'm sure I've seen, in one of the tabloids, a very, very, very large rat. The tabloids love pictures of absolutely huge things. I think go for 1.5 feet.

Matt - Okay. 1.5 feet.

Julia - 1.5 feet is indeed correct. Imagine seeing a rat that was 1.5 feet. If I see a normal rat, I'm just on a chair somewhere so 1.5 feet, I just pass out. The research essentially found it was impossible to create many of the key genes needed to resurrect the Christmas Island rats because certain parts of the code have been lost over time. This includes some genes related to the rat's sense of smell. Why is a sense of smell important for resurrecting an animal? Is it a) smell guides behavioural impulses, like mating and fighting, b) the animals would eat poisonous food by accident, or c) rats are blind so they need smell to navigate?

Matt - c) is not true so it must be a). a) feels sensible to me.

Fiona - Yeah. I like a).

Matt - You'd always just raise them in a research environment and not feed them poison.

Julia - You would be spot on. The answer is a) smell is very important for animals behaviour in general, much more than it is for us. That's why it's very important that these animals, if they were resurrected, have the proper smell genes that they would've had in the wild. Amazing. We're now onto the very last topic and sorry Kit and Mary-Frances. You don't get a choice. You've got Wrecks.

News story - [https://www.thenakedscientists.com/articles/interviews/endurance-discove...

Julia - The wreck of Ernest Shackleton's Endurance was discovered after 107 years following its sinking on the sea floor of the Weddell Sea in Antarctica. The ship was found to be in relatively pristine condition, considering it's been sat there for a century. What conditions did not contribute to the endurance being found intact? Is it a) the cold water, b) a lack of wood eating worms, or c) weak currents?

Kit - I know that down there you can't get the worms because it's too cold and it's an anaerobic environment for them. There's nothing down there. But there are no weak currents around Antarctica. I've been in Cape Horn. That is not a weak current. I think that that's probably the red herring there. What do you think?

Mary-Frances - Well, that sounds convincing to me. I'll go with that.

Julia - Yes. Kit, you've used your lived experience to get yourself a point because yes c) weak currents. They thought it's the cold water and the lack of those worms being there. Have you seen the pictures? It looks incredible.

Kit - It looks pristine.

Julia - Endurance is one of many shipwrecks in the world's oceans and seas. How many shipwrecks are thought to be sitting on the beds of our waters? Is a) 300,000 b) 3 million or c) 13 million.

Kit - Worldwide?

Julia - Yep. Across the entire world.

Mary-Frances - It's got to be quite a lot. Think of the hundreds of years we've been sending ships around.

Kit - I would imagine there's probably 300,000 just around the UK to be perfectly honest. There's a lot of shipping. I'd probably be going for the millions. What do you think? 13 million. Should we go high?

Mary-Frances - I think 13 million.

Kit - Let's go 13 million.

Julia - The answer is b) 3 million. Not quite 13 million, but still millions worldwide. That's obviously an estimation because they think less than 1% have actually been found and explored. When a ship sinks, it becomes part of the ecosystem and sea creatures take up residence amongst the decks and that creates this artificial reef. What is one thing artificial reefs are designed to be used for? Is it a) to increase catch for commercial fishing, b) to give fish a more stimulating environment, or c) to move fish, to allow for altered water temperatures?

Mary-Frances - Ooh... I don't know. Maybe a)? I think that would be something people would like to be able to create environments for commercial fishing. But I don't know. What do you think Kit?

Kit - I don't think it's b). I don't think we just like to entertain fish. Unless it's Finding Nemo, that's probably not what we do. I'm tempted by c) because I'm thinking about things like The Great Barrier Reef where you're seeing a lot of bleaching of the corals and maybe they're trying to move it into other areas. That's something that I could see people doing.

Mary-Frances - Yeah. You're convincing me Kit. I think c). I like c).

Kit - Let's go for c).

Julia - The correct answer is c) to move fish to allow for altered water temperatures. They're making these artificial reefs and they said, it's really good that they can look at shipwrecks as an example, and then you can show that we can make these artificial reefs and move them. The fish will go where the reef goes, and that allows for us to get fish into the temperature of water that they should be in. I think we have a winner and the winners are Kit and Mary Francis. Well done. Good job. We did have a tiebreaker, but we didn't need it. I think it was only by 1 point?

Kit - 1 point. Yeah.

Mary-Frances - Well, that might have been a tie.

53:23 - Quick fire questions!

Quick fire questions!

Mary-Frances O’Connor, University of Arizona & Kit Chapman, Falmouth University & Matt Bothwell, University of Cambridge & Fiona Fox, Science Media Centre

Julia Ravey speaks with Mary-Frances O’Connor, Kit Chapman, Matt Bothwell & Fiona Fox to find the answers to your submitted questions...

Julia - Mary-Frances, Jenny asked 'If someone close to you is going through grief, how can you best support them?'

Mary-Frances - Often people think the goal is to cheer them up, but actually that often creates more feeling of distance. The person is already under this really dense cloud. Really the goal should be more to just be with them, and to let them know that there is a future and you will be with them there as well, even when they can't quite envision it yet.

Julia - Now Kit over to you. Paul asked 'How much do you think formula 1 cars will change over the coming years with advancing technology based on how much they've changed in the past?'

Kit - Hugely. We are looking at moving to probably an entirely new fuel system. The ICE, the internal combustion engine, won't be around much longer. We're looking at a carbon neutral sport within the next 8-10 years. They're gonna start looking at alternative fuels. Maybe that's electric, maybe that's hydrogen, maybe that's synthetic hydrocarbons, but you will not see petrol in formula 1 cars in 5 years time.

Julia - Fiona. We've got a science media question for you here. Don's asked, 'Do platforms like Twitter do more harm than good when it comes to communicating science news?'

Fiona - No, I don't think they do more harm than good. I don't think we know that. There's a huge amount of good, accurate evidence based information on social media platforms. Many, many people share links to great science on Twitter. I don't think it does more harm than good. I think it has the potential to do harm and that's why we are asking scientists to get out there and use social media and engage with mainstream media and make sure they drown out the voices of harmful misinformation.

Julia - Brilliant. Matt, finally over to you. We've got a question from Lewis who asks very simply, 'What are your thoughts on space tourism?'

Matt - I think it's going to happen whether we like it or not. I think if billionaires want to go into space, they're going to do whatever they want. I think to be honest, it's a little bit of a distraction right now. I think there's a lot of exciting things going on in the space technology industry and just a handful of billionaires having joy rides up to the upper atmosphere is not particularly interesting. I'm not very interested in it to be honest, compared to a lot of other stuff going on in the space tech industry.

Related Content

- Previous Return to the Moon

- Next Sex

Comments

Add a comment